Bois non traité sous pression

Bois traité sans pression Pour la plupart des bois traités, les produits de préservation sont appliqués sous pression dans des installations spéciales. Cependant, il arrive que cela ne soit pas possible ou que la nécessité de traiter le bois ne soit apparue qu'après la construction ou l'occupation du bâtiment. Dans ce cas, les produits de préservation peuvent être appliqués en utilisant des méthodes qui ne font pas appel à des cuves sous pression. Certains de ces traitements ne peuvent être effectués que par des applicateurs agréés. Lors de l'utilisation de produits de préservation du bois, comme pour tous les pesticides, il convient de respecter les exigences de l'Agence de réglementation de la lutte antiparasitaire (au Canada) ou de l'Agence de protection de l'environnement (aux États-Unis) en matière d'étiquetage. Cinq catégories de traitements sans pression Traitement pendant la fabrication des produits en bois d'ingénierie Certains produits en bois d'ingénierie, tels que le contreplaqué et le bois de placage stratifié (LVL), peuvent être traités après fabrication avec des solutions de préservation, alors que les produits à base de fines lamelles (OSB, OSL) et les panneaux à base de petites particules et de fibres (panneaux de particules, MDF) ne peuvent pas l'être. Les produits de préservation doivent être ajoutés aux éléments en bois avant qu'ils ne soient collés ensemble, sous forme de pulvérisation, de brouillard ou de poudre. Les produits tels que l'OSB sont fabriqués à partir de petites et fines lamelles de bois. Les conservateurs en poudre peuvent être mélangés aux brins et aux résines pendant le processus de mélange, juste avant le formage et le pressage du matelas. Le borate de zinc est couramment utilisé dans cette application. En ajoutant des conservateurs au processus de fabrication, il est possible d'obtenir un traitement uniforme sur toute l'épaisseur du produit. En Amérique du Nord, le contreplaqué est normalement protégé contre la pourriture et les termites par des procédés de traitement sous pression. Toutefois, dans d'autres parties du monde, des insecticides sont souvent formulés avec des adhésifs pour protéger le contreplaqué contre les termites. Prétraitement de surface Il s'agit d'un traitement de préservation anticipé appliqué par trempage, pulvérisation ou brossage sur toutes les surfaces accessibles de certains produits en bois au cours du processus de construction. L'objectif est de fournir une enveloppe de protection aux produits, composants ou systèmes en bois vulnérables dans leur forme finie. Un exemple serait la pulvérisation de borates sur les charpentes des maisons pour les rendre résistantes aux termites de bois sec et aux coléoptères xylophages dans certains cas. Ces traitements peuvent également être appliqués au bois d'œuvre, au contreplaqué et à l'OSB afin de fournir une protection supplémentaire contre la formation de moisissures. Prétraitement sous la surface (Depot treatment) Il s'agit d'un traitement de préservation appliqué à des endroits distincts, et non à l'ensemble de la pièce, au cours du processus de fabrication ou de la construction. L'objectif est de protéger de manière proactive uniquement les parties du produit, de l'élément ou du système en bois susceptibles d'être exposées à des conditions propices à la pourriture. Un exemple serait de placer des tiges de borate dans les trous percés dans les extrémités exposées des poutres en lamellé-collé dépassant la ligne de toit. Traitement complémentaire Il s'agit d'un traitement de préservation appliqué à des endroits distincts sur du bois traité en service pour compenser une pénétration initiale incomplète de la section transversale ou une diminution de l'efficacité de la préservation au fil du temps. L'objectif est de renforcer la protection du bois déjà traité ou de traiter les zones exposées par la coupe nécessaire des produits en bois traité. Un exemple serait l'application d'un pansement prêt à l'emploi sur des poteaux électriques dont la charge conservatrice d'origine s'est épuisée. Un autre exemple est celui des matériaux coupés sur place pour les fondations en bois préservé. Traitement correctif Il s'agit d'un traitement de préservation appliqué au bois sain résiduel dans les produits, les composants ou les systèmes où l'on sait que la pourriture ou les attaques d'insectes ont commencé. L'objectif est de tuer les champignons ou les insectes existants et/ou d'empêcher la pourriture ou les insectes de se propager au-delà des dommages existants. Un exemple serait l'application au rouleau ou par pulvérisation d'une formulation de borate/glycol sur du bois sain laissé en place à côté d'une charpente pourrie (qui devrait être découpée et remplacée par du bois traité sous pression). Formes des traitements sans pression Les traitements sans pression se présentent sous trois formes différentes : solides, liquides/pâteux et fumigants. Contrairement aux produits de préservation traités sous pression, qui dépendent de la pression pour une bonne pénétration, ces produits dépendent de la mobilité des ingrédients actifs pour pénétrer suffisamment profondément dans le bois pour être efficaces. Les ingrédients actifs peuvent se déplacer dans le bois par capillarité ou se diffuser dans l'eau et/ou l'air à l'intérieur du bois. Cette mobilité permet non seulement aux substances actives de pénétrer dans le bois, mais aussi de s'en échapper dans certaines conditions. Cela signifie que les conditions à l'intérieur et autour de la structure doivent être comprises afin de minimiser la perte de conservateur et la perte de protection qui en découle. Les borates, les fluorures et les composés de cuivre sont particulièrement adaptés à une utilisation sous forme de solides, de liquides et de pâtes. L'isothiocyanate de méthyle (et ses précurseurs), le bromure de méthyle et le fluorure de sulfuryle sont les seuls traitements par fumigation largement utilisés. Le bromure de méthyle a été éliminé en 2005, sauf pour des utilisations très limitées. Solides Le principal avantage des solides dans ces applications est qu'ils maximisent la quantité de matière soluble dans l'eau qui peut être placée dans un trou foré, en raison du pourcentage élevé d'ingrédients actifs contenus dans les tiges disponibles dans le commerce. L'inconvénient majeur est la nécessité d'une humidité suffisante et le temps nécessaire à la dissolution de la tige. Le système de préservation solide le plus ancien et le plus connu est la tige de borate fondu, développée à l'origine dans les années 1970 pour le traitement complémentaire et correctif des traverses de chemin de fer. Ils ont depuis été utilisés avec succès sur les poteaux électriques, les bois de construction, les menuiseries (fenêtres) et une variété d'autres produits en bois. Un mélange de borates est fusionné en verre à des températures extrêmement élevées, puis versé dans un moule et laissé à prendre. Placé dans des trous dans le bois, le borate se dissout dans l'eau contenue dans le bois et se diffuse dans toute la région humide. L'écoulement en masse de l'humidité le long du grain peut accélérer la distribution du borate. Des biocides secondaires tels que le cuivre peuvent être ajoutés aux tiges de borate pour compléter l'efficacité des borates contre la pourriture et les insectes. Bien que tous les conservateurs doivent être traités avec respect, de nombreux utilisateurs se sentent plus à l'aise avec les tiges de borate et de cuivre/borate en raison de leur faible toxicité et de leur faible potentiel de pénétration dans l'organisme. Les fluorures sont également disponibles sous forme de bâtonnets. Le bâtonnet est produit en comprimant du fluorure de sodium et des liants, ou en l'encapsulant dans un tube perméable à l'eau. Les fluorures se diffusent plus rapidement que les borates dans l'eau et peuvent également se déplacer en phase vapeur sous forme d'acide fluorhydrique. Le borate de zinc (ZB) est une poudre

Bois traité sous pression

Le bois traité avec des produits de conservation est généralement traité sous pression, c'est-à-dire que les produits chimiques sont introduits sur une courte distance dans le bois à l'aide d'un récipient spécial qui combine la pression et le vide. Bien qu'une pénétration en profondeur soit hautement souhaitable, la nature imperméable des cellules de bois mort rend extrêmement difficile l'obtention de quelque chose de plus qu'une fine couche de bois traité. Les principaux résultats du processus de traitement sous pression sont la quantité de produit de conservation imprégnée dans le bois (appelée rétention) et la profondeur de pénétration. Ces caractéristiques du traitement sont spécifiées dans des normes axées sur les résultats. Une plus grande pénétration du produit de conservation peut être obtenue par incision - un procédé qui consiste à percer de petites fentes dans le bois. Ce procédé est souvent nécessaire pour les matériaux de grande taille ou difficiles à traiter afin de respecter les normes de pénétration basées sur les résultats. Les procédés de traitement sous pression varient en fonction du type de bois traité et du produit de préservation utilisé. En général, le bois est d'abord conditionné pour éliminer l'excès d'eau qu'il contient. Il est ensuite placé dans un récipient sous pression et un vide est fait pour éliminer l'air à l'intérieur des cellules du bois. Ensuite, le conservateur est ajouté et une pression est appliquée pour faire pénétrer le conservateur dans le bois. Enfin, la pression est relâchée et un dernier vide est appliqué pour éliminer et réutiliser l'excès de conservateur. Après le traitement, certains systèmes de conservation, tels que le CCA, nécessitent une étape de fixation supplémentaire afin de s'assurer que le produit de conservation a complètement réagi avec le bois. Des informations sur les différents types de produits de préservation utilisés sont disponibles dans la rubrique Durabilité par traitement.

Sécurité incendie

Le Code national du bâtiment du Canada (CNB) définit la sécurité incendie dans l'objectif OS1 : "l'un des objectifs du présent code est de limiter la probabilité qu'en raison de la conception ou de la construction du bâtiment, une personne se trouvant dans le bâtiment ou à proximité de celui-ci soit exposée à un risque inacceptable de blessure en raison d'un incendie". En termes plus simples, la sécurité incendie est la réduction du risque d'atteinte à la vie humaine résultant d'un incendie dans les bâtiments. Bien que le risque d'être tué ou blessé dans un incendie ne puisse être complètement éliminé, la sécurité incendie dans un bâtiment peut être obtenue grâce à des caractéristiques de conception éprouvées visant à minimiser autant que possible le risque d'atteinte à l'intégrité physique par le feu. Concevoir un bâtiment pour garantir un risque minimal ou pour atteindre un niveau prescrit de sécurité contre l'incendie est plus complexe que la simple prise en compte des matériaux de construction qui seront utilisés dans la construction du bâtiment, puisque tous les matériaux de construction sont affectés par le feu. De nombreux facteurs doivent être pris en compte, notamment l'utilisation du bâtiment, le nombre d'occupants, la facilité avec laquelle ils peuvent sortir du bâtiment en cas d'incendie et la manière dont un incendie peut être circonscrit. Même les matériaux qui ne résistent pas au feu ne garantissent pas la sécurité d'une structure. L'acier, par exemple, perd rapidement sa résistance lorsqu'il est chauffé et sa limite d'élasticité diminue considérablement à mesure qu'il absorbe la chaleur, ce qui met en péril la stabilité de la structure. Un système de plancher à poutrelles en acier formé à froid, non protégé, se rompt en moins de 10 minutes selon les méthodes d'essai d'exposition au feu en laboratoire, alors qu'un système de plancher à poutrelles en bois, non protégé, peut durer jusqu'à 15 minutes. Le béton armé n'est pas non plus à l'abri du feu. Le béton s'effrite sous l'effet de températures élevées, exposant l'armature en acier et affaiblissant les éléments structurels. Par conséquent, il est généralement admis qu'il n'existe pas vraiment de bâtiment à l'épreuve du feu. Le CNB ne réglemente que les éléments qui font partie de la construction du bâtiment. Le contenu d'un bâtiment n'est généralement pas réglementé par le CNB, mais dans certains cas, il est réglementé par le Code national de prévention des incendies du Canada (CNPI). La classification des bâtiments ou parties de bâtiments en fonction de leur utilisation prévue tient compte de la quantité et du type de contenu combustible susceptible d'être présent (charge d'incendie potentielle), du nombre de personnes susceptibles d'être exposées à la menace d'un incendie, de la superficie du bâtiment et de sa hauteur. Cette classification est le point de départ pour déterminer quelles exigences de sécurité incendie s'appliquent à un bâtiment particulier. La classification de l'occupation d'un bâtiment au sein du CNB dicte : le type de construction du bâtiment ; le niveau de protection contre l'incendie ; et le degré de protection structurelle contre la propagation du feu entre les parties d'un bâtiment qui sont utilisées à des fins différentes. Les incendies peuvent survenir dans n'importe quel type de structure. La gravité d'un incendie dépend toutefois de la capacité d'une construction à : confiner le feu ; limiter les effets d'un incendie sur la structure porteuse ; et contrôler la propagation de la fumée et des gaz. À des degrés divers, tout type de construction peut être conçu comme un système (combinaison d'ensembles de construction) pour limiter les effets du feu. Cela permet aux occupants de disposer de suffisamment de temps pour évacuer le bâtiment et aux pompiers de s'acquitter de leurs tâches en toute sécurité. La sécurité des occupants dépend également d'autres paramètres tels que la détection, les voies d'évacuation et l'utilisation de systèmes d'extinction automatique d'incendie tels que les sprinklers. Ces concepts constituent la base des exigences du CNB. Pour de plus amples informations, veuillez consulter les ressources suivantes : Wood Design Manual (Conseil canadien du bois) Fire Safety Design in Buildings (Conseil canadien du bois) Code national du bâtiment du Canada Code national de prévention des incendies du Canada CSA O86, Engineering design in wood Fitzgerald, Robert W., Fundamentals of Fire Safe Building Design, Fire Protection Handbook, National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA, 1997. Watts, J.M. (Jr) ; Systems Approach to Fire-Safe Building Design, Fire Protection Handbook, National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, MA, 2008. Rowe, W.D. ; Assessing the Risk of Fire Systemically ASTM STP 762, Fire Risk Assessment, American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA, 1982.

Propagation de la flamme

La propagation de la flamme est principalement une caractéristique de combustion superficielle des matériaux, et l'indice de propagation de la flamme est un moyen de comparer la vitesse de propagation de la flamme à la surface d'un matériau par rapport à un autre. Les exigences en matière d'indice de propagation de la flamme sont appliquées dans le Code national du bâtiment du Canada (CNB), principalement pour réglementer les finitions intérieures. Tout matériau faisant partie de l'intérieur du bâtiment et directement exposé est considéré comme une finition intérieure. Cela comprend les revêtements intérieurs, les planchers, les moquettes, les portes, les garnitures, les fenêtres et les éléments d'éclairage. Si aucun revêtement n'est installé du côté intérieur d'un mur extérieur d'un bâtiment, les surfaces intérieures de l'ensemble des murs sont considérées comme la finition intérieure, par exemple, une construction à poteaux et à poutres non finie. De même, si aucun plafond n'est installé sous un plancher ou un toit, le tablier et les éléments structuraux exposés non finis sont considérés comme la finition intérieure du plafond. La méthode d'essai normalisée à laquelle le CNB fait référence pour la détermination des indices de propagation de la flamme est la norme CAN/ULC-S102, publiée par ULC Standards. L'annexe D-3 de la division B du CNB fournit des renseignements sur les indices génériques de propagation de la flamme et les classifications de dégagement de fumée de divers matériaux de construction. Ces informations ne concernent que les matériaux génériques pour lesquels il existe de nombreuses données d'essais au feu (voir le tableau 1 ci-dessous). Par exemple, le bois d'œuvre, quelle que soit l'essence, et le contreplaqué de sapin de Douglas, de peuplier et d'épicéa, d'une épaisseur au moins égale à celles indiquées, se voient attribuer un indice de propagation de la flamme de 150. En général, pour les produits en bois d'une épaisseur inférieure à 25 mm (1 pouce), l'indice de propagation de la flamme diminue avec l'augmentation de l'épaisseur. Les valeurs indiquées dans l'annexe D du CNB sont prudentes car elles sont destinées à couvrir une large gamme de matériaux. Des essences et des épaisseurs spécifiques peuvent avoir des valeurs bien inférieures à celles indiquées dans l'annexe D. Les valeurs spécifiques par essence de bois sont indiquées dans la fiche d'information sur l'inflammabilité des surfaces et la propagation des flammes, ci-dessous. Des informations sur les matériaux brevetés et ignifuges sont disponibles auprès d'organismes de certification et d'homologation tiers ou auprès des fabricants. Les valeurs indiquées dans la fiche d'information sur l'inflammabilité de surface et la propagation de la flamme s'appliquent au bois d'œuvre fini ; toutefois, aucune différence significative n'a été observée dans l'indice de propagation de la flamme du bois d'œuvre brut de sciage de la même essence. L'American Wood Council fournit des informations complémentaires dans sa publication Design for Code Acceptance, DCA 1 Flame Spread Performance of Wood Products for the U.S. Normalement, la finition de la surface et le matériau sur lequel elle est appliquée contribuent tous deux à la performance globale en matière de propagation de la flamme. La plupart des revêtements de surface tels que la peinture et le papier peint ont généralement une épaisseur inférieure à 1 mm et ne contribuent pas de manière significative à l'évaluation globale. C'est pourquoi le CNB attribue le même indice de propagation de la flamme et de dégagement des fumées à des matériaux courants tels que le contreplaqué, le bois de construction et les plaques de plâtre, qu'ils soient bruts ou recouverts de peinture, de vernis ou de papier peint cellulosique. Il existe également des peintures et des revêtements ignifuges spéciaux qui peuvent réduire considérablement l'indice de propagation de la flamme d'une surface intérieure. Ces revêtements sont particulièrement utiles lors de la réhabilitation d'un bâtiment ancien pour réduire l'indice de propagation de la flamme des matériaux de finition à des niveaux acceptables, en particulier pour les zones nécessitant un indice de propagation de la flamme inférieur ou égal à 25. En général, le CNB fixe à 150 l'indice maximal de propagation de la flamme pour les finitions intérieures des murs et des plafonds, ce qui peut être respecté par la plupart des produits en bois. Par exemple, le contreplaqué de sapin Douglas de 6 mm (1/4 po) peut être non fini, peint, verni ou recouvert d'un papier peint cellulosique conventionnel. Cette solution a été jugée acceptable sur la base de l'expérience réelle en matière d'incendie. Cela signifie que dans toutes les zones où un indice de propagation de la flamme de 150 est autorisé, la majorité des produits en bois peuvent être utilisés comme finitions intérieures sans exigences particulières en matière de traitements ou de revêtements ignifuges. Lors d'un incendie dans une pièce, le revêtement de sol est généralement le dernier élément à s'enflammer, car la couche d'air la plus froide se trouve à proximité du sol. C'est pourquoi le CNB, comme la plupart des autres codes, ne réglemente pas l'indice de propagation de la flamme des revêtements de sol, à l'exception de certaines zones essentielles dans les bâtiments de grande hauteur : les sorties, les couloirs ne se trouvant pas dans les suites, les cabines d'ascenseurs et les locaux techniques. Les matériaux de revêtement de sol traditionnels, tels que les parquets et les moquettes, peuvent être utilisés presque partout dans les bâtiments, quel que soit leur type de construction. Pour plus d'informations, consultez les ressources suivantes : Wood Design Manual (Conseil canadien du bois) Fire Safety Design in Buildings (Conseil canadien du bois) Code national du bâtiment du Canada Code national de prévention des incendies du Canada CSA O86, Engineering design in wood CAN/ULC-S102 Standard Method of Test for Surface Burning Characteristics of Building Materials and Assemblies American Wood Council Tableau 1 : Indices de propagation de la flamme et classifications du dégagement de fumée attribués Indices d'inflammabilité et de propagation de la flamme de la surface

Résistance au feu

Dans le Code national du bâtiment du Canada (CNB), le " degré de résistance au feu " est défini en partie comme suit : "le temps, en minutes ou en heures, pendant lequel un matériau ou un assemblage de matériaux résiste au passage des flammes et à la transmission de la chaleur lorsqu'il est exposé au feu dans des conditions d'essai et selon des critères de performance spécifiés..." Le degré de résistance au feu est le temps, en minutes ou en heures, pendant lequel un matériau ou un assemblage de matériaux résiste au passage des flammes et à la transmission de la chaleur lorsqu'il est exposé au feu dans des conditions d'essai et selon des critères de performance spécifiés, ou tel que déterminé par l'extension ou l'interprétation des informations qui en découlent, comme le prescrit le CNB. Les critères d'essai et d'acceptation mentionnés dans le CNB sont contenus dans une méthode d'essai au feu normalisée, CAN/ULC-S101, publiée par ULC Standards. Les assemblages horizontaux tels que les planchers, les plafonds et les toits sont testés pour l'exposition au feu par le dessous seulement. Cela s'explique par le fait qu'un incendie dans le compartiment inférieur représente la menace la plus grave. C'est pourquoi le degré de résistance au feu est exigé uniquement pour la face inférieure de l'ensemble. Le degré de résistance au feu de l'ensemble testé indiquera, dans le cadre des limites de conception, les conditions de retenue de l'essai. Lors de la sélection d'un degré de résistance au feu, il est important de s'assurer que les conditions de contrainte de l'essai sont les mêmes que celles de la construction sur le terrain. Les assemblages à ossature en bois sont normalement testés sans contrainte d'extrémité afin de correspondre à la pratique normale de la construction. Les cloisons ou les murs intérieurs qui doivent avoir un degré de résistance au feu doivent être évalués de la même manière de chaque côté, car un incendie peut se développer de part et d'autre de la séparation coupe-feu. Elles sont normalement conçues de manière symétrique. S'ils ne sont pas symétriques, le degré de résistance au feu de l'ensemble est déterminé sur la base d'essais effectués du côté le plus faible. Pour un mur porteur, l'essai exige que la charge maximale autorisée par les normes de conception soit superposée à l'ensemble. La plupart des murs à ossature bois sont testés et répertoriés comme porteurs. Cela leur permet d'être utilisés à la fois dans des applications porteuses et non porteuses. Les listes de murs porteurs à ossature bois peuvent être utilisées pour des cas non porteurs puisque les mêmes ossatures sont utilisées dans les deux cas. Le chargement pendant l'essai est critique car il affecte la capacité de l'assemblage de murs à rester en place et à remplir sa fonction de prévention de la propagation du feu. La perte de résistance des montants résultant de températures élevées ou de la combustion réelle d'éléments structurels entraîne une déformation. Cette déformation affecte la capacité des membranes de protection des murs (plaques de plâtre) à rester en place et à contenir le feu. Le degré de résistance au feu des murs porteurs est généralement inférieur à celui d'un mur non porteur de conception similaire. Les murs extérieurs n'ont besoin d'être classés que pour l'exposition au feu depuis l'intérieur du bâtiment. En effet, l'exposition au feu depuis l'extérieur d'un bâtiment n'est probablement pas aussi grave que celle d'un incendie dans une pièce ou un compartiment intérieur. Comme ce classement n'est exigé que pour l'intérieur, les murs extérieurs ne doivent pas nécessairement être symétriques. Le CNB permet à l'autorité compétente d'accepter les résultats d'essais au feu effectués conformément à d'autres normes. Comme les méthodes d'essai ont peu changé au fil des ans, les résultats basés sur des éditions antérieures ou plus récentes de la norme CAN/ULC-S101 sont souvent comparables. La principale norme américaine en matière de résistance au feu, l'ASTM E119, est très similaire à la norme CAN/ULC-S101. Toutes deux utilisent la même courbe temps-température et les mêmes critères de performance. Les taux de résistance au feu établis conformément à la norme ASTM E119 sont généralement acceptés par les autorités canadiennes. L'acceptation par l'autorité compétente des résultats des essais basés sur ces normes dépend principalement de la familiarité de l'autorité avec ces normes. Les laboratoires d'essais et les fabricants publient également des informations sur des listes de produits exclusives qui décrivent les matériaux utilisés et les méthodes d'assemblage. Une multitude d'essais de résistance au feu ont été réalisés au cours des 70 dernières années par des laboratoires nord-américains. Les résultats sont disponibles sous forme de listes ou de rapports de conception par l'intermédiaire de : APA Intertek QAI Laboratories PSF Corporation Laboratoires des assureurs du Canada Underwriters' Laboratories Incorporated En outre, les fabricants de produits de construction publient les résultats d'essais de résistance au feu sur des ensembles incorporant leurs propres produits (par exemple, le GA-600 Fire Resistance Design Manual de la Gypsum Association). Le CNB contient des informations génériques sur la résistance au feu des assemblages et des éléments en bois. Il comprend des tableaux de résistance au feu et au bruit décrivant divers assemblages de murs et de planchers constitués de matériaux de construction génériques et attribuant des degrés de résistance au feu spécifiques à ces assemblages. Au cours des deux dernières décennies, le Conseil national de recherches du Canada (CNRC) a mené un certain nombre de grands projets de recherche sur les murs et les planchers à ossature légère, portant à la fois sur la résistance au feu et sur la transmission du son. Le CNB dispose ainsi de centaines de murs et de planchers différents auxquels sont attribués des degrés de résistance au feu et des indices de transmission du son. Ces résultats sont publiés dans le tableau A-9.10.3.1.A. Résistance au feu et au bruit des murs et dans le tableau A-9.10.3.1.B Résistance au feu et au bruit des planchers, plafonds et toits du CNB. Les assemblages décrits n'ont pas tous fait l'objet d'essais. Les degrés de résistance au feu de certains assemblages ont été extrapolés à partir d'essais de résistance au feu effectués sur des assemblages de murs similaires. Les listes sont utiles parce qu'elles offrent aux concepteurs des solutions standard. Elles peuvent toutefois restreindre l'innovation car les concepteurs utilisent des assemblages qui ont déjà été testés plutôt que de payer pour que de nouveaux assemblages soient évalués. Les assemblages répertoriés doivent être utilisés avec les mêmes matériaux et les mêmes méthodes d'installation que ceux qui ont été testés. La section précédente sur les degrés de résistance au feu traite de la détermination des degrés de résistance au feu à partir d'essais standard. D'autres méthodes de détermination des degrés de résistance au feu sont également autorisées. Les méthodes alternatives de détermination des degrés de résistance au feu sont contenues dans l'annexe D du CNB, division B, intitulée "Fire Performance Ratings". Ces méthodes de calcul alternatives peuvent remplacer les essais de résistance au feu propriétaires coûteux. Dans certains cas, elles permettent d'appliquer des exigences moins strictes en matière d'installation et de conception, telles que d'autres détails de fixation pour les plaques de plâtre et l'autorisation d'ouvertures dans les membranes de plafond pour les systèmes de ventilation. La section D-2 de l'annexe D de la division B du CNB comprend des méthodes d'attribution de degrés de résistance au feu aux murs, planchers et toits à ossature en bois dans l'annexe D-2.3 (méthode d'addition des composants) ; aux murs, planchers et toits en bois massif dans l'annexe D-2.4 ; et aux poutres en bois lamellé-collé.

Chantiers de construction

La vulnérabilité d'un bâtiment en cas d'incendie est plus élevée pendant la phase de construction que lorsqu'il est achevé et occupé. Cela s'explique par le fait que les risques et les dangers présents sur un chantier de construction diffèrent, tant par leur nature que par leur impact potentiel, de ceux qui existent dans un bâtiment achevé. En outre, ces risques et dangers surviennent à un moment où les éléments de prévention et de protection contre l'incendie qui sont conçus pour faire partie du bâtiment achevé ne sont pas encore en place. Pour ces raisons, la sécurité incendie sur les chantiers de construction comporte des défis uniques. Toutefois, la compréhension des dangers et des risques potentiels constitue la première étape de la prévention et de l'atténuation des incendies. Il est important de se conformer aux réglementations applicables en matière de planification de la sécurité incendie pendant la construction, et la coopération entre toutes les parties prenantes dans l'établissement et la mise en œuvre d'un plan contribue grandement à réduire le risque potentiel et les conséquences d'un incendie sur un chantier de construction. Outre les réglementations provinciales, les gouvernements locaux et les municipalités peuvent également avoir des lois, des réglementations ou des exigences spécifiques qui doivent être respectées. Le service local de lutte contre les incendies peut être une ressource pour vous orienter vers ces règlements ou exigences supplémentaires. La sécurité sur les chantiers de construction peut avoir un impact sur la productivité et la rentabilité à n'importe quelle phase du projet. Étant donné que les réglementations provinciales ou municipales constituent les exigences minimales en matière de sécurité incendie sur les chantiers de construction, il convient également de prendre en considération les caractéristiques, les objectifs et les buts spécifiques du projet, qui pourraient inciter à dépasser les normes réglementées en matière de sécurité incendie sur les chantiers de construction. Il peut être prudent d'évaluer et de mettre en œuvre diverses "meilleures pratiques", basées sur les besoins spécifiques de votre chantier, qui peuvent fournir un niveau de protection supplémentaire et instaurer une culture de la sécurité incendie. La plupart des incendies de chantier peuvent être évités grâce aux connaissances, à la planification et à la diligence, et l'impact des incendies qui peuvent se produire peut être considérablement réduit. Comprendre et traiter les dangers et les risques généraux et spécifiques d'un chantier de construction particulier nécessite une éducation et une formation, ainsi qu'une préparation et une vigilance permanentes. Pour de plus amples informations, veuillez consulter les ressources suivantes : "Sécurité incendie sur les chantiers de construction : A Guide for Construction of Large Buildings" - par le Centre for Public Safety and Criminal Justice Research, University of the Fraser Valley pour CWC, 2015 "Construction Site Fire Response : Report on Course of Construction (Fire) Best Practices Guide" - par Technical Risk Services pour la CCB, 2014 "Comparison of the Canadian Construction Site Fire Safety Regulations/Guidelines" - par Sereca pour la CCB, 2014 Quick Facts - Insurance and Construction Series (CWC, 2005) : "No. 1 - Cours sur l'assurance construction - Principes de base" No. 2 - Cours sur le contrôle des risques de construction" No. 3 - Cours sur la construction - Lignes directrices sur le contrôle des risques de chantier" "Sécurité incendie et sûreté : Note technique sur la sécurité incendie et la sécurité sur les chantiers de construction en Colombie-Britannique" - par Wood Works ! British Columbia, 2013 City of Surrey, BC - Construction Fire Safety Plan Bulletin Fire Safety During Construction of Five and Sixy Wood Buildings in Ontario : A Best Practice Guideline - par le ministère des Affaires municipales et du Logement de l'Ontario, mai 2016 "Fire Safety and Security : Note technique sur la sécurité-incendie sur les chantiers de construction en Ontario - par Wood Works ! Ontario, 2013

Conception structurelle

Une structure doit être conçue pour résister à toutes les charges qui devraient agir sur elle pendant sa durée de vie. Sous l'effet des charges appliquées prévues, la structure doit rester intacte et fonctionner de manière satisfaisante. En outre, la construction d'une structure ne doit pas nécessiter une quantité démesurée de ressources. La conception d'une structure est donc un équilibre entre la fiabilité nécessaire et l'économie raisonnable. Les produits du bois sont fréquemment utilisés pour fournir les principaux moyens de soutien structurel des bâtiments. L'économie et la solidité de la construction peuvent être obtenues en utilisant des produits du bois comme éléments de structure tels que les solives, les montants muraux, les chevrons, les poutres, les poutrelles et les fermes. En outre, les produits de revêtement et de platelage en bois jouent à la fois un rôle structurel en transférant les charges du vent, de la neige, des occupants et du contenu aux principaux éléments structurels, et une fonction d'enveloppe du bâtiment. Le bois peut être utilisé dans de nombreuses formes structurelles telles que les maisons à ossature légère et les petits bâtiments qui utilisent des éléments répétitifs de petite dimension ou dans des systèmes d'ossature structurelle plus grands et plus lourds, tels que la construction en bois de masse, qui est souvent utilisée pour les projets commerciaux, institutionnels ou industriels. La conception technique des composants et systèmes structuraux en bois est basée sur la norme CSA O86. Au cours des années 1980, la conception des structures en bois au Canada, conformément au Code national du bâtiment du Canada (CNB) et à la norme CSA O86, est passée de la conception des contraintes de travail (WSD) à la conception des états limites (LSD), rendant l'approche de la conception structurelle pour le bois similaire à celle des autres principaux matériaux de construction. Toutes les méthodes de calcul structurel exigent les éléments suivants pour la résistance et l'aptitude au service : Résistance des éléments = Effets des charges de calcul En utilisant la méthode LSD, la structure et ses composants individuels sont caractérisés par leur résistance aux effets des charges appliquées. Le CNB applique des facteurs de sécurité à la fois au côté résistance et au côté charge de l'équation de calcul : Résistance pondérée = Effet de charge pondéré La résistance pondérée est le produit d'un facteur de résistance (f) et de la résistance nominale (résistance spécifiée), tous deux fournis dans la norme CSA O86 pour les matériaux et les assemblages en bois. Le facteur de résistance tient compte de la variabilité des dimensions et des propriétés des matériaux, de l'exécution, du type de défaillance et de l'incertitude dans la prédiction de la résistance. L'effet de la charge pondérée est calculé conformément au CNB en multipliant les charges réelles sur la structure (charges spécifiées) par des facteurs de charge qui tiennent compte de la variabilité de la charge. Il n'existe pas deux échantillons de bois ou de tout autre matériau ayant exactement la même résistance. Dans tout processus de fabrication, il est nécessaire de reconnaître que chaque pièce fabriquée sera unique. Les charges, telles que la neige et le vent, sont également variables. Par conséquent, la conception structurelle doit tenir compte du fait que les charges et les résistances sont en réalité des groupes de données plutôt que des valeurs uniques. Comme pour tout groupe de données, il existe des attributs statistiques tels que la moyenne, l'écart-type et le coefficient de variation. L'objectif de la conception est de trouver un équilibre raisonnable entre la fiabilité et des facteurs tels que l'économie et l'aspect pratique. La fiabilité d'une structure dépend d'une série de facteurs qui peuvent être classés comme suit : influences externes telles que les charges et les changements de température ; modélisation et analyse de la structure, interprétations du code, hypothèses de conception et autres jugements qui constituent le processus de conception ; résistance et cohérence des matériaux utilisés dans la construction ; et qualité du processus de construction. L'approche LSD consiste à fournir une résistance adéquate à certains états limites, à savoir la résistance et l'aptitude au service. Les états limites de résistance font référence à la capacité de charge maximale de la structure. Les états limites d'aptitude au service sont ceux qui restreignent l'utilisation et l'occupation normales de la structure, comme une déflexion ou des vibrations excessives. Une structure est considérée comme défaillante ou impropre à l'utilisation lorsqu'elle atteint un état limite au-delà duquel ses performances ou son utilisation sont compromises. Les états limites pour la conception du bois sont classés dans les deux catégories suivantes : Les états limites ultimes (ELU) concernent la sécurité des personnes et correspondent à la capacité de charge maximale. Ils comprennent des défaillances telles que la perte d'équilibre, la perte de capacité de charge, l'instabilité et la rupture ; et les états limites d'aptitude au service (ELS) concernent les restrictions de l'utilisation normale d'une structure. Les états limites d'aptitude au service (ELS) concernent les restrictions de l'utilisation normale d'une structure. En raison des propriétés naturelles uniques du bois, telles que la présence de nœuds, la flache ou la pente du grain, l'approche de la conception pour le bois nécessite l'utilisation de facteurs de modification spécifiques au comportement structurel. Ces facteurs de modification sont utilisés pour ajuster les résistances spécifiées dans la norme CSA O86 afin de tenir compte des caractéristiques du matériau propres au bois. Les facteurs de modification couramment utilisés dans le calcul des structures en bois comprennent les effets de la durée de la charge, les effets de système liés aux éléments répétitifs agissant ensemble, les facteurs de conditions de service humides ou sèches, les effets de la taille des éléments sur la résistance et l'influence des produits chimiques et du traitement sous pression. Les systèmes de construction en bois ont des rapports résistance/poids élevés et les constructions en bois à ossature légère contiennent de nombreux petits connecteurs, le plus souvent des clous, qui offrent une ductilité et une capacité importantes pour résister aux charges latérales, telles que les tremblements de terre et le vent. Les murs de cisaillement et les diaphragmes à ossature légère constituent une solution de contreventement latéral très courante et pratique pour les bâtiments en bois. Généralement, le revêtement en bois, le plus souvent du contreplaqué ou des panneaux à copeaux orientés (OSB), qui est spécifié pour résister à la charge de gravité, peut également faire office de système de résistance aux forces latérales. Cela signifie que le revêtement remplit plusieurs fonctions, notamment la distribution des charges aux solives du plancher ou du toit, le contreventement des poutres et des montants pour éviter qu'ils ne se déforment et la résistance latérale aux charges dues au vent et aux tremblements de terre. D'autres systèmes de résistance aux charges latérales sont utilisés dans les bâtiments en bois, notamment les cadres rigides ou les portiques, les contreventements à genoux et les contreventements transversaux. Un tableau des portées typiques est présenté ci-dessous pour aider le concepteur à choisir un système structurel en bois approprié. Pour de plus amples informations, veuillez consulter les ressources suivantes : Introduction à la conception en bois (Conseil canadien du bois) Manuel de conception en bois (Conseil canadien du bois) CSA O86 Conception technique en bois Code national du bâtiment du Canada www.woodworks-software.com

Propriétés du bois d'œuvre

Pendant de nombreuses années, les valeurs de calcul des bois de construction canadiens ont été déterminées en testant de petits échantillons clairs. Bien que cette approche ait bien fonctionné dans le passé, certains éléments indiquaient qu'elle ne reflétait pas toujours fidèlement le comportement en service d'un élément de taille normale. À partir des années 1970, de nouvelles données ont été recueillies sur le bois d'œuvre calibré de taille normale, connu sous le nom d'essais en cours de fabrication. Au début des années 1980, l'industrie canadienne du bois a mené un important programme de recherche dans le cadre du Programme des propriétés du bois du Conseil canadien du bois pour déterminer les propriétés de résistance à la flexion, à la traction et à la compression parallèle au fil du bois de 38 mm d'épaisseur (2 pouces nominaux) de tous les groupes d'essences canadiennes commercialement importants. Le Lumber Properties Program a été mené en coopération avec l'industrie américaine dans le but de vérifier la corrélation de la classification du bois d'une usine à l'autre, d'une région à l'autre et entre le Canada et les États-Unis. Le programme d'essais en cours d'utilisation a consisté à tester des milliers de pièces de bois de construction jusqu'à leur destruction afin de déterminer leurs caractéristiques en cours d'utilisation. Il a été convenu que ce programme d'essai devait simuler, aussi fidèlement que possible, les conditions structurelles d'utilisation finale auxquelles le bois serait soumis. Après avoir été conditionnés à un taux d'humidité d'environ 15 %, les échantillons ont été soumis à des charges à court et à long terme conformément à la norme ASTM D4761. Des échantillons de bois de trois dimensions : 38 x 89 mm, 38 x 184 mm et 38 x 235 mm (2 x 4 po, 2 x 8 po et 2 x 10 po) ont été sélectionnés dans les régions de culture canadiennes pour les trois groupes d'essences commerciales les plus importants : épicéa-pin-sapin (S-P-F), douglas-sapin-mélèze (D.Fir-L) et sapin-épicéa. Les essences Select Structural, No.1, No.2, No.3, ainsi que les essences de charpente légère, ont été échantillonnées en flexion. Les qualités Select Structural, No.1 et No.2 ont été évaluées en traction et en compression parallèlement au fil. Plusieurs essences de moindre volume ont également été évaluées à des intensités d'échantillonnage plus faibles. Les essais en cours d'exploitation ont permis d'établir de nouvelles relations entre les essences, les dimensions et les qualités. La base de données des résultats du bois de construction a été examinée afin d'établir les tendances des propriétés de flexion, de tension et de compression parallèlement au grain, en fonction de la taille et de la qualité de l'élément. Ces études ont permis d'étendre les résultats à l'ensemble des qualités de bois d'oeuvre et des dimensions des éléments décrits dans la norme CSA O86. Au Canada, la norme CSA O86 et le Code national du bâtiment du Canada (CNB) ont adopté les résultats du Programme des propriétés du bois de sciage. Les données ont également été utilisées pour mettre à jour les valeurs de calcul aux États-Unis. Les données scientifiques issues du Lumber Properties Program ont démontré : une corrélation étroite entre les propriétés de résistance des bois de dimension n° 1 et n° 2 classés visuellement ; une bonne corrélation dans l'application des règles de classement d'une usine à l'autre et d'une région à l'autre ; et une diminution de la résistance relative à mesure que la taille augmente (effet de taille) - par exemple, la résistance unitaire à la flexion d'un élément de 38 × 89 mm (2 x 4 pouces) est supérieure à celle d'un élément de 38 × 114 mm (2 x 6 pouces). À la suite du programme d'essais, la norme ASTM D1990, fondée sur un consensus, a été élaborée et publiée. Les données relatives à la flexion, à la traction parallèle au fil, à la compression parallèle au fil et au module d'élasticité continuent d'être analysées conformément à cette norme. Contrairement au bois d'œuvre classé visuellement, dont les propriétés de résistance anticipées sont déterminées à partir de l'évaluation d'une pièce sur la base de l'aspect visuel et de la présence de défauts tels que les nœuds, les flaches ou l'inclinaison du grain, les caractéristiques de résistance du bois d'œuvre classé sous contrainte mécanique (MSR) sont déterminées en appliquant des forces à un élément et en mesurant réellement la rigidité d'une pièce particulière. Lorsque le bois est alimenté en continu dans l'équipement d'évaluation mécanique, la rigidité est mesurée et enregistrée par un petit ordinateur, et la résistance est évaluée par des méthodes de corrélation. Le classement MSR peut être effectué à des vitesses allant jusqu'à 365 m (1000 ft) par minute, y compris l'apposition d'une marque de classement MSR. Le bois de MSR fait également l'objet d'un contrôle visuel des propriétés autres que la rigidité qui pourraient affecter l'adéquation d'une pièce donnée. Étant donné que la rigidité de chaque pièce est mesurée individuellement et que la résistance est mesurée sur des pièces sélectionnées dans le cadre d'un programme de contrôle de la qualité, le bois de MSR peut se voir attribuer des résistances de conception spécifiées plus élevées que le bois de dimension classé visuellement. Pour de plus amples informations, veuillez consulter les ressources suivantes : ASTM D1990 Standard Practice for Establishing Allowable Properties for Visually-Graded Dimension Lumber from In-Grade Tests of Full-Size Specimens ASTM D4761 Standard Test Methods for Mechanical Properties of Lumber and Wood-Based Structural Materials National Lumber Grades Authority (NLGA)

Fondations permanentes en bois

Une fondation permanente en bois (CPB) est un système de construction technique qui utilise des murs porteurs extérieurs en bois à ossature légère dans une application sous le niveau du sol. Une fondation permanente en bois se compose d'un mur à colombages et d'une sous-structure de semelle, construits en contreplaqué et en bois d'œuvre traités avec un agent de conservation approuvé, qui soutiennent une superstructure située au-dessus du niveau du sol. En plus de fournir un support structurel vertical et latéral, le système PWF offre une résistance aux flux de chaleur et d'humidité. Les premiers exemples de PWF ont été construits dès 1950 et nombre d'entre eux sont encore utilisés aujourd'hui. Le PWF est un système technique solide, durable et éprouvé qui présente un certain nombre d'avantages uniques, notamment économies d'énergie grâce à des niveaux d'isolation élevés, réalisables par l'application d'une isolation des cavités des montants et d'une isolation extérieure rigide (jusqu'à 20% de transfert de chaleur peuvent se produire à travers la fondation) ; espace de vie sec et confortable fourni par un système de drainage supérieur (qui ne nécessite pas de tuiles de drainage) ; espace de vie accru puisque les cloisons sèches peuvent être fixées directement aux montants des murs de fondation ; résistance à la fissuration due aux cycles de gel et de dégel ; adaptables à la plupart des conceptions de bâtiments, y compris les vides sanitaires, les ajouts et les sous-sols accessibles par l'extérieur ; un seul corps de métier requis pour un calendrier de construction plus efficace ; constructibles en hiver avec une protection minimale autour des semelles pour les protéger du gel ; construction rapide, qu'il s'agisse d'une ossature sur place ou d'une préfabrication hors site ; les matériaux sont facilement disponibles et peuvent être expédiés efficacement vers des sites de construction ruraux ou éloignés ; et longue durée de vie, basée sur l'expérience acquise sur le terrain et par les ingénieurs. Les MPO conviennent à tous les types de construction à ossature légère visés par la partie 9 " Maisons et petits bâtiments " du Code national du bâtiment du Canada (CNB), c'est-à-dire que les MPO peuvent être utilisés pour des bâtiments d'une hauteur maximale de trois étages au-dessus des fondations et dont la surface de construction n'excède pas 600 m2. Les MPO peuvent être utilisés comme systèmes de fondation pour les maisons unifamiliales, les maisons en rangée, les appartements de faible hauteur et les bâtiments institutionnels et commerciaux. Ils peuvent également être conçus pour des projets tels que les vides sanitaires, les ajouts de pièces et les fondations de murs de genoux pour les garages et les maisons préfabriquées. Il existe trois types différents de PWF : le sous-sol à dalle de béton ou à plancher de bois, le sous-sol à plancher de bois suspendu et le vide sanitaire non excavé ou partiellement excavé. Les montants de bois utilisés dans les CPE sont généralement de 38 x 140 mm (2 x 6 pouces) ou de 38 x 184 mm (2 x 8 pouces), de qualité n° 2 ou supérieure. Des méthodes améliorées de contrôle de l'humidité autour et sous le PWF permettent d'obtenir un espace de vie confortable et sec sous le niveau du sol. Le coffrage est placé sur une couche de drainage granulaire qui s'étend sur 300 mm au-delà des semelles. Un pare-vapeur extérieur, appliqué à l'extérieur des murs, assure la protection contre les infiltrations d'humidité. Les joints calfeutrés entre tous les panneaux muraux extérieurs en contreplaqué et au bas des murs extérieurs ont pour but de contrôler les fuites d'air à travers le PWF, mais aussi d'éliminer les voies de pénétration de l'eau. Le résultat est un sous-sol sec qui peut être facilement isolé et aménagé pour un maximum de confort et d'économies d'énergie. Tout le bois d'œuvre et le contreplaqué utilisés dans un PWF, à l'exception d'éléments ou de conditions spécifiques, doivent être traités à l'aide d'un produit de préservation du bois à base d'eau et identifiés comme tels par une marque de certification attestant de leur conformité à la norme CSA O322. Les clous résistants à la corrosion, les ancrages d'ossature et les sangles utilisés pour fixer les matériaux traités à l'aide d'un produit de préservation du bois doivent être galvanisés par immersion à chaud ou en acier inoxydable. Les pare-vapeur et les pare-humidité extérieurs doivent avoir une épaisseur d'au moins 0,15 mm (6 mil). Les panneaux de drainage à excroissances sont souvent utilisés comme pare-vapeur extérieur. Pour plus d'informations, consultez les références suivantes : Fondations permanentes en bois (Conseil canadien du bois) Fondations permanentes en bois 2023 - Durable, confortable, adaptable, économe en énergie, économique (Préservation du bois Canada et Conseil canadien du bois) Manuel de conception du bois (Conseil canadien du bois) Préservation du bois Canada CSA S406 Spécification des fondations permanentes en bois pour les habitations et les petits bâtiments CSA O322 Procédure de certification des matériaux en bois traité sous pression utilisés dans les fondations permanentes en bois CSA O86 Conception technique en bois Code national du bâtiment du Canada

Durabilité par conception

La "durabilité par la conception" est l'aspect le plus important des solutions durables. Il s'agit d'abord d'utiliser du bois sec, de le stocker de manière appropriée pour s'assurer qu'il reste sec, puis de concevoir le bâtiment de manière à protéger le bois ou, si le bois est exposé, de le concevoir de manière à ce qu'il n'accumule pas d'humidité. Il faut également veiller à ce que l'enveloppe du bâtiment soit conçue de manière à évacuer l'eau en vrac, à empêcher l'eau et la vapeur de pénétrer dans l'enveloppe et à évacuer l'eau qui s'y infiltre.

Durabilité par nature

Pour les applications extérieures du bois, nous avons une forte tradition, ici en Amérique du Nord, d'utilisation de nos essences naturellement durables : le Western Red Cedar, le Eastern White Cedar, le cyprès jaune et le séquoia. Ce sont des choix familiers pour les terrasses, les clôtures, les bardages et les toitures. Ces essences sont résistantes à la décomposition à l'état naturel, en raison de leur teneur élevée en produits chimiques organiques appelés matières extractibles. Les extractibles sont des substances chimiques qui se déposent dans le bois de cœur de certaines espèces d'arbres lors de la transformation de l'aubier en bois de cœur. Outre le fait qu'elles confèrent au bois une résistance à la pourriture, les substances extractives donnent souvent au bois de cœur une couleur et une odeur. Seul le bois de cœur possède ces dépôts protecteurs. L'aubier de tous les résineux d'Amérique du Nord est sensible à la pourriture et doit être protégé par d'autres moyens lorsqu'une résistance à la pourriture est nécessaire. L'aubier est la partie la plus récente de l'arbre, plus proche de l'écorce. Il n'a pas besoin d'être protégé contre la pourriture dans l'arbre vivant, car les réactions à la blessure empêchent tout organisme envahissant de pénétrer dans l'arbre. Le bois de cœur est la partie interne, plus ancienne de l'arbre, qui n'est plus vivante. Le bois de cœur se distingue souvent visiblement de l'aubier par sa couleur (le bois de cœur est généralement plus foncé), mais ce n'est pas le cas pour toutes les espèces. Cependant, même si vous êtes sûr d'avoir du bois de cœur d'une espèce durable, il se peut que vous n'ayez pas le niveau de résistance que vous pensez. La résistance à la pourriture est souvent très variable et peut être plus faible dans les arbres cultivés en plantation. Il n'existe actuellement aucun moyen d'estimer de manière fiable la durabilité d'un morceau de bois de cœur naturellement durable. Plus d'informations Cliquez ici pour obtenir un tableau indiquant les classements de durabilité naturelle des essences de bois tendre les plus courantes.

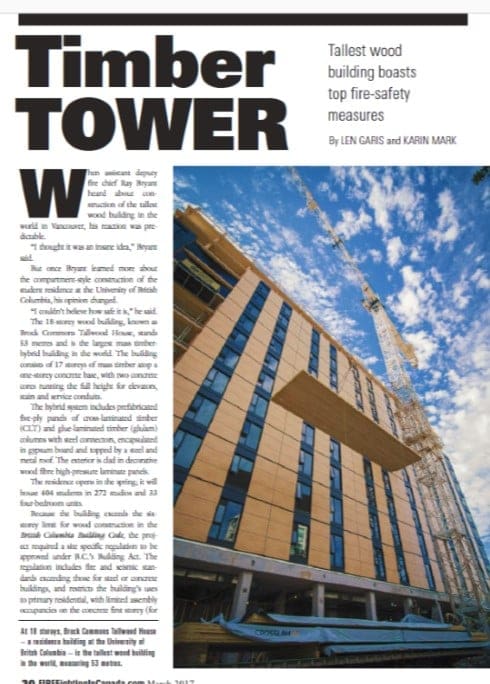

Article sur la lutte contre l'incendie au Canada - Timber Tower

Article de Len Garis et Karin Mark.

Lorsque Ray Bryant, chef adjoint des pompiers, a entendu parler de la construction du plus haut bâtiment en bois du monde à Vancouver, sa réaction était prévisible. "J'ai pensé que c'était une idée folle", a déclaré Bryant. Mais lorsqu'il a appris que la résidence étudiante de l'université de Colombie-Britannique était construite dans le style d'un compartiment, il a changé d'avis. "Je n'arrivais pas à croire à quel point c'était sûr", a-t-il déclaré. Lire l'article.