An Industry Average EPD for Canadian Softwood Plywood

A Regionalized Industry Average EPD for Canadian Oriented Strand Board

A Regionalized Industry Average EPD for Canadian Softwood Lumber

Guide to Encapsulated Mass Timber Construction in the Ontario Building Code

The Guide to Encapsulated Mass Timber Construction in the Ontario Building Code – Second Edition is a comprehensive resource designed to help designers, code officials, and building professionals understand and apply the latest Ontario Building Code provisions for Encapsulated Mass Timber Construction (EMTC), effective January 1, 2025. Developed by the Canadian Wood Council / WoodWorks Ontario in collaboration with Morrison Hershfield (now Stantec), the guide explains the technical requirements, fire safety principles, and design considerations unique to EMTC, with clear references to relevant OBC articles. It covers everything from structural mass timber element specifications and encapsulation materials, to use and occupancy limits, mixed-use scenarios, and related provisions for structural design, environmental separation, and fire safety during construction. Intended to be read in conjunction with the Ontario Building Code, this is not a design guide, but rather a tool to distill complex regulations into practical, accessible information—equipping professionals to confidently design, review, and approve EMTC projects while ensuring compliance and optimizing performance. Notice of Correction: A previous version of this document contained a small error on page 19. In this electronic version of the document (updated August 12, 2025) the 3rd major bullet of Section 5.1.1 has been corrected.

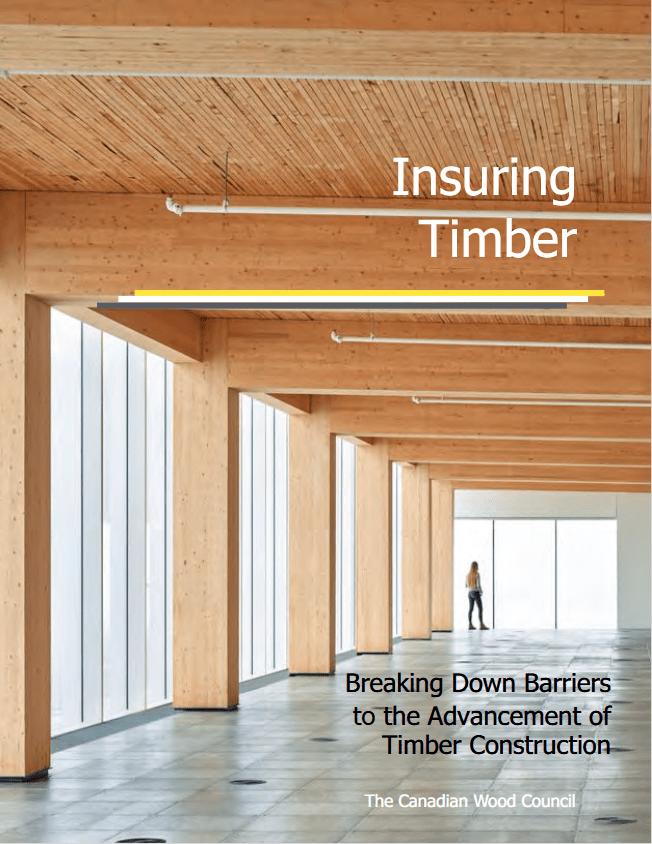

Insuring Timber Strategy

2023 CWC Annual Report

ICC-ES Listing report for self-tapping screws for Canada

The ICC-ES Listing Report for Self-Tapping Screws for Canada provides third-party evaluation and listing information for self-tapping screws intended for use in Canadian construction applications. The document is intended for designers, engineers, specifiers, and code officials who require verified compliance information to support product approval and specification. The report outlines evaluated products, applicable standards, and conditions of use relevant to Canadian building codes and regulatory requirements. It serves as a reference for understanding the scope of the listing, including performance attributes, installation parameters, and limitations associated with the evaluated self-tapping screw systems. Developed as a compliance and reference document, the ICC-ES Listing Report supports informed decision-making and facilitates code acceptance for self-tapping screws used in wood and hybrid construction in Canada.

Long-Span CLT Floors: the importance of under floor insulation for soundproofing

This Rothoblaas document explores the role of underfloor insulation in improving acoustic performance in long-span cross-laminated timber (CLT) floor systems. Intended for designers, engineers, and building professionals, the document addresses key soundproofing challenges associated with larger spans and exposed timber structures. The document explains how underfloor insulation contributes to reducing airborne and impact sound transmission, with discussion of system behaviour, material selection, and integration with CLT floor assemblies. It also highlights design and construction considerations that influence acoustic performance, including detailing, installation quality, and coordination with other building systems. Developed as a technical reference, this document supports informed design decisions for long-span CLT floors, helping project teams achieve acoustic comfort while maintaining structural and architectural objectives.

Hybrid buildings: what they are and why they’re gaining ground in the construction industry

This Rothoblaas document examines the growing use of hybrid building systems and the factors driving their increased adoption across the construction industry. Intended for architects, engineers, and construction professionals, the document provides an overview of how wood is combined with materials such as steel and concrete to achieve performance, efficiency, and design objectives. The document outlines common hybrid building configurations, key structural and construction considerations, and the benefits these systems can offer, including improved constructability, structural efficiency, and project flexibility. It also explores why hybrid approaches are gaining traction, particularly in response to evolving building codes, sustainability goals, and project delivery demands. Developed as an educational resource, this document supports a clearer understanding of hybrid construction strategies, helping project teams evaluate when and how hybrid systems can be effectively applied in contemporary building projects.

Structural retrofitting techniques and fire safety regulations for structures in glulam

This Rothoblaas document provides an overview of structural retrofitting strategies for glulam buildings, with a focus on meeting fire safety regulations and performance requirements. Intended for engineers, designers, and building professionals, the document addresses key considerations when upgrading or reinforcing existing glulam structures. The document explores common retrofitting techniques, connection solutions, and system-level interventions that can enhance structural capacity while maintaining compliance with fire safety objectives. It also examines how fire regulations influence retrofit design decisions, including material selection, detailing, and protection strategies for glulam elements. Developed as a technical reference, this document supports informed retrofit planning and design, helping project teams balance structural performance, fire safety, and regulatory compliance when working with existing glulam structures.

Timber screws and connections: preventing failure through correct installation

This Rothoblaas document explores the critical role that correct installation plays in the performance and reliability of timber screws and structural connections. Aimed at designers, engineers, and construction professionals, the document highlights how improper installation practices can compromise load capacity, durability, and overall structural performance in wood construction. The document examines common causes of connection failure, including incorrect screw selection, installation angle, spacing, and edge distances. It also outlines best practices and practical considerations to help ensure timber screws and connections perform as intended, from design through on-site installation. Developed as an educational resource, this document supports improved understanding of connection behaviour in timber structures, helping project teams reduce risk, improve build quality, and achieve reliable performance through proper installation techniques.

Privacy Policy

We are pleased to open our Call for Entries and invite North American and International submissions to the 2025 Wood Design and Building Awards program celebrating excellence in wood architecture and construction. The Canadian Wood Council (“CWC”) is committed to upholding the confidentiality and security of your personal information. The CWC respects your right to privacy and have instituted best practices to help ensure that your personal information is handled responsibly. This Policy explains how CWC collects, uses, and discloses personal information that you knowingly provide while using this website and website content (the “Website”) and in any electronic publications, newsletters, or announcements made by it (“Electronic Communications”). By using CWC’s Web sites, you consent to our collection, use, and disclosure of the information you provide, as set out in this Privacy Policy. Any personal information provided to CWC through the Web sites will be treated with care, and subject to this Policy will not be used or disclosed in ways not consented. 1. Scope of this Policy 2. Information Automatically Collected 3. Personal Information You Specifically Provide to the Website 4. Other Matters Your Comments — If you have any comments or questions about this Policy or your personal information, please contact CWC at helpdesk@cwc.ca. Other Websites — The Website may contain links to other Websites or Internet resources. When you click on one of those links you are contacting another Website or Internet resource that may collect information about you voluntarily or through cookies or other technologies. CWC has no responsibility or liability for, or control over those other Websites or Internet resources or their collection, use and disclosure of your personal information. Website Terms of Use — The Terms of Use governing your use of the Website contains important provisions disclaiming and excluding the liability of CWC and others regarding your use of the Website and provisions determining the applicable law and exclusive jurisdiction for the resolution of any disputes regarding your use of the Website. Each of those provisions also applies to any disputes that may arise in relation to this Policy and the collection, use and disclosure of your personal information, and are of the same force and effect as if they had been reproduced directly in this Policy. Former Users — If you stop using the Website or your permission to use the Website is terminated by CWC, CWC may continue to use and disclose your personal information in accordance with this Policy as amended from time to time, and subject to compliance with the law. Privacy Policy Changes — This Policy may be changed by CWC from time to time, without any prior notice or liability to you or any other person. The collection, use and disclosure of your personal information by CWC will be governed by the version of this Policy in effect at that time. New versions of this Policy will be posted here. Your continued use of the Website and receipt or request of any electronic communication subsequent to any changes to this Policy will signify that you consent to the collection, use and disclosure of your personal information in accordance with the changed Policy. Accordingly, when you use the Website or receive or request any electronic communication, you should check the date of this Policy and review any changes since the last version.